2025 Making your Business Antifragile Part Two

2025 Businesses living in a whole new world. Find your business in the graph and begin your innovation journey.

First, a perspective:

Gregor Mendel (1822-1884)

Mendel's laws of inheritance and principles of genetics, published in 1866, were largely ignored by the scientific community. His work was rediscovered around 1900, 16 years after his death, becoming the foundation of modern genetics.

Alfred Wegener (1880-1930)

Wegener proposed the theory of continental drift in 1912, suggesting continents had once been joined. Geologists ridiculed his theory for decades. Only in the 1950s and 1960s, long after his death, did plate tectonics confirm his core insight.

Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920)

Many of Ramanujan's mathematical formulas and theories were so advanced that mathematicians couldn't fully understand them during his lifetime. Decades after his early death, his notebooks continue to inspire new mathematical discoveries.

Emmy Noether (1882-1935)

Noether's theorem, connecting symmetries in physics with conservation laws, was not widely recognized during her lifetime, partly due to gender discrimination. Today, it's considered one of the most important mathematical theorems relevant to physics.

W. Ross Ashby (1903-1972)

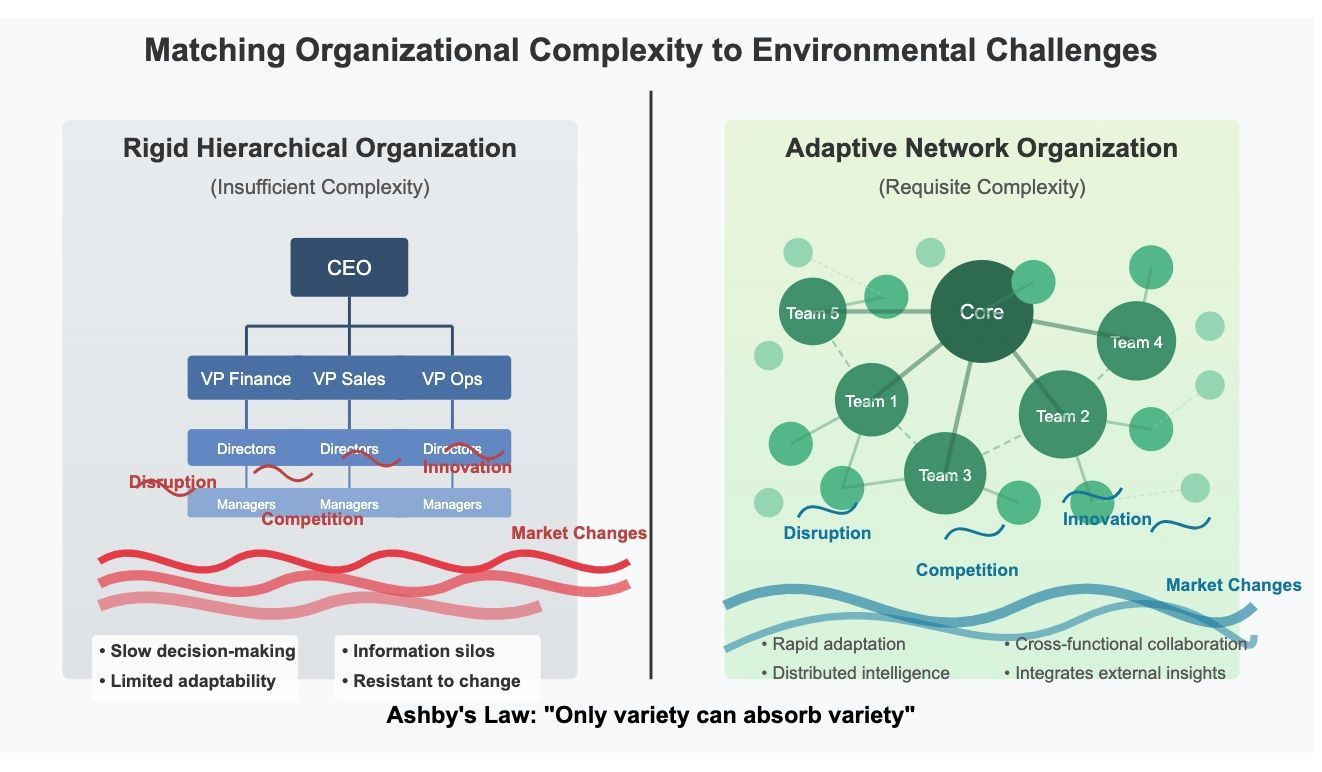

Following this pattern of visionaries whose insights were not fully appreciated in their time, Ashby proposed a principle that was always true but not fully understood: "Only variety can absorb (manage) variety."

Translated to today's business context: 2025 businesses require a complex operating model sufficient for handling the complexity of the environment they operate in.

Ashby's Principle and Modern Business

Ashby, a psychiatrist and pioneer in cybernetics, warned against the appealing but ultimately ineffective promise of simple solutions to complex problems, while offering a path forward through embracing necessary complexity in our response systems.

In today's context of climate change, technological disruption, global pandemics, and social polarization, this principle illuminates the requirement for systems thinking rather than reductionist approaches.

Ashby's work was particularly influential during a time when systems theory was emerging as a cross-disciplinary approach to understanding complex systems, from biological organisms to social organizations and mechanical systems.

Ashby explored how adaptive behavior emerges in complex systems. His work focused on understanding the mechanisms that allow a system (like a brain) to be both stable and adaptable. He was influential in the emerging fields of cybernetics, systems theory, and in artificial intelligence. He approached the study of the brain not only from a biological perspective, but as a system with particular properties that could be understood through mathematical and logical analysis. His work predates current neuroscience research. Recent neuroscientific findings now validate many aspects of his framework, long after his death. (Reference 1)

The Ashby Line

The Ashby line, also known as the Law of Requisite Variety, is a fundamental principle in systems theory. This principle states that for a system to be stable and effectively controlled, the controlling system must have at least as much variety (or complexity) as the system being controlled. In other words, "only variety can absorb (manage) variety."

The Ashby line represents the minimum complexity needed in a regulator (business operating model) to effectively manage a given system. If the regulator (business operating model) has less variety than the system it aims to control, it will inevitably fail to handle all possible states or disturbances the system might encounter.

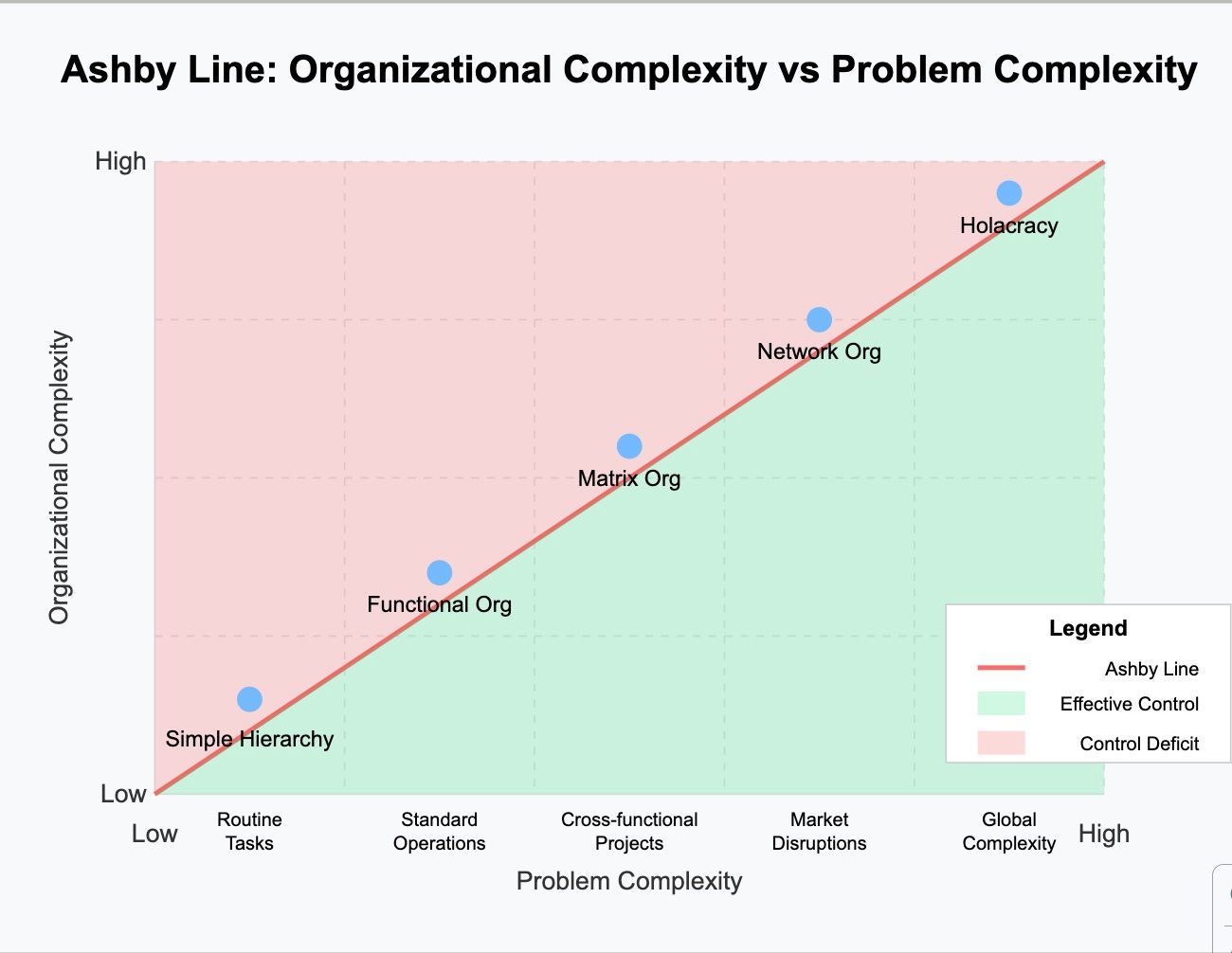

Ashby Line Graph - Where is your organization positioned in this graph? Where do you perceive the complexity of your environment to be positioned?

Organizational Complexity vs Problem Complexity

- The Ashby Line (red diagonal) represents the minimum organizational complexity required to effectively handle a given level of problem complexity

- Two zones:

- Green zone (below the line): Where organizational complexity is sufficient to manage the problems faced

- Red zone (above the line): Where problems exceed the organization's capacity to handle them effectively

- Organizational structures along the spectrum:

- Simple hierarchies work for routine, predictable challenges

- Functional organizations handle standard operations with moderate complexity

- Matrix organizations manage cross-functional projects and competing priorities

- Network organizations address market disruptions and rapid changes

- Holacracy and other highly adaptive structures tackle global, interconnected challenges

Many traditional organizations struggle with today's rapidly changing, interconnected problems – their business models simply lack the requisite variety needed to respond effectively to increasing environmental complexity.

What Failure Looks Like

So, what does it look like when your organization is NOT modeled to manage the environment; when your organization is unable to change the strategic direction necessary to meet the environmental complexity requirements?

Loss of Control

- Old operating business models failing to identify unique customer complaints, and early warning signs of trouble

- Surprising declines or stagnation in revenue, without a clear understanding of why

- Traditional quarterly planning cycles unable to respond to rapidly changing consumer preferences

- Centralized decision-making structures where individual contributing employees see problems but lack authority to address them or they lack a process to inform senior leadership

Over Simplification in Strategy

- Companies restricting which markets they operate in to maintain control

- Overly strict policies that eliminate exceptions in an effort to maintain the costs in a business

- Refusing to adopt new technologies but instead maintain familiar processes

- Artificial constraints on product offerings to reduce operational complexity

Over Indexing on Complexity (without a clear model)

- Organizations stuck in perpetual restructuring as they try to match environmental complexity

- Rapidly expanding management layers and committees

- Explosion of specialized roles and departments

- Increasing technology investments without corresponding organizational changes

Case Studies

Six Sigma organizations and General Electric

GE developed increasingly complex management structures, including the notorious "rank and yank" performance system and Six Sigma implementation across all divisions. While initially successful, this extreme internal complexity eventually created a bureaucratic organization that struggled to innovate. By focusing on process optimization and complex control systems, GE lost its ability to respond to market disruptions. The company that was once the world's most valuable eventually faced severe decline, losing over 80% of its market value by 2018. The system failed to take advantage of the optimization wins and then pivot to take advantage of the next innovation.

Microsoft under Steve Ballmer

Microsoft created a complex matrix organization with competing business divisions that required extensive coordination. The company became infamous for its "stack ranking" system that forced managers to rate some employees as underperforming regardless of actual performance. This organizational complexity generated political infighting rather than innovation, causing Microsoft to miss major market transitions to mobile and cloud computing despite having the technical capabilities.

Conversely, Microsoft's transformation under Satya Nadella successfully transformed from a Windows-centric company to a cloud and services provider by fundamentally restructuring its organization. Nadella eliminated the competitive divisional structure, created cross-functional teams, and implemented a curious culture. This increase in internal complexity matched the increasing external complexity of the tech ecosystem.

Apple and Sony

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he famously reduced the product lineup by approximately 70%, focusing on just four products. While this appears to contradict Ashby's Law, it actually demonstrates intentional management of complexity - simplifying customer-facing elements while building complexity where it mattered (in design and user experience).

On the other side, Sony in the 2000s responded to increasing market complexity by creating an extremely complex organizational structure with hundreds of subsidiaries and business units. Different divisions developed competing products (VAIO computers, PlayStation, phones, and tablets all had separate operating systems). This overamplification created internal competition rather than collaboration, decision paralysis, and inability to create integrated products to compete with Apple's simpler but more effective ecosystem approach.

Summary

Contrary to past logic, businesses succeeding today aren't necessarily the largest or best-funded—they're the ones whose internal complexity enables them to sense, respond to, and shape their environment. The question isn't whether your environment is becoming more complex—it is. The question is whether your organization is evolving to match it.

If you are interested in the operating system of the future, sufficient to manage the complexity of the environment, see our blog post on FutureProof™.

Reference 1: For a list of the innovators and scientists who have used Ashby's work as a foundation in their work, consult (ask AI about) additional resources on systems theory. His work has been influential across multiple disciplines, and his ideas have been cited extensively in:

- Systems theory and cybernetics literature

- Organizational science

- Information theory

- Complexity science

- Artificial intelligence and robotics

- Management theory